In 1851, 11 year old George W. Riddle and his family embarked upon a six-month journey from Illinois to settle in “one of the most beautiful little valleys in the world.”

Excerpt from History of Early Days in Oregon, By George W. Riddle

Chapter 13

It was near the first of November 1851 that we settled upon the land now known as Glenbrook Farms. Our tents were pitched under the oak tree now standing just north of the Glenbrook farmhouse. At that time Cow Creek Valley looked like a great wheat field. The Indians, according to their custom, had burned the grass during the summer, and early rains had caused a luxuriant crop of grass on which our emigrant cattle were fat by Christmastime.

We had finally, after six months of travel, reached the promised land, and although we had settled in one of the most beautiful little valleys in the world, our nearest neighbor was eight miles away, and only four homes within twenty-five miles. This seemed out of the world to my two older sisters, and I remember there were tears and waitings that we had left Illinois and endured all the hardships of the plains to settle down in a place where they would never see anyone and never have any neighbors. However, the homesickness was soon forgotten and all were busy in arranging a camp for the winter.

One large tent and one small one were set up and two of the wagon boxes were arranged on the ground which with the covers made a sleeping place, and canvas was spread to shelter the cook stove. I would say here that that stove was brought from Illinois with us. There was a compartment arranged in the back part of one of our wagons for the stove and it was lifted out and set up at every camp. This stove must have been a wonder–our family at that time, with two extra men, were fifteen in number and all with outdoor appetites.

Immediately after our camp was arranged the work of preparing a home was begun. A house must be built, fields must be fenced, and all material must be hewn or split from the primitive forest.

Fortunately, in our case the land was ready for the plow. There was no grubbing to do. In all the low valleys of the Umpqua there was very little undergrowth, the annual fires set by the Indians preventing young growth of timber, and fortunately there was plenty of material on hand for house and fencing.

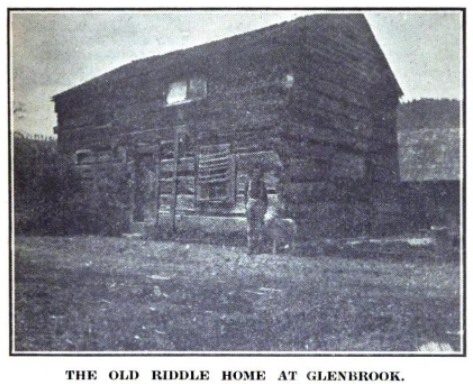

On the bench land north of the Glenbrook Farms was a grove of pines from which logs were hewn for a house. We boys, with the ox teams. hauled the hewed logs to the site for the house. I think I might here, for the benefit of some of the younger readers, explain in what manner and what kind of houses the pioneers built.

The first thing the emigrant did on arriving in Oregon was to select a claim. The next was to build a house. The only material for the house was logs, for at [the] time of which I write there was not a saw mill in Southern Oregon. Many of the houses were built of round logs sufficient to shelter the family. Floors were made of split boards and called “puncheon floor.”

In the course of time as the settler required more house room, he would build a second house the same dimensions as the first, sixteen or more feet from the first. This was always called “the other house.” The space between the two houses was roofed and was used for various purposes. This style of house was called a Missouri house. It was characteristic of this house, as well as all pioneer houses, for the latch string to always be out. That is to say that the pioneer was noted for his hospitality. My father was more ambitious than the average pioneer.

Our house was made of “hewed” logs, was about 18×30 and a story and a half high with a shed on one side enclosed with shakes full length for a kitchen and dining room, with a great stack of a stone chimney built on the outside at the east end, with a double fireplace, one inside and one outside. The outside fireplace was built with the intention of adding an addition to the house.

It was well along in the spring of 1852 that our house was ready for occupancy. Fortunately for us the winter had been a mild one. Snow had hardly covered the ground, and I remember my mother commenting on winter with no ice thicker than a window pane, so though we had lived the winter through in tents, we were comparatively comfortable.

The Indians had been friendly, bringing us fish and venison which they would exchange for any old thing. Game was in abundance, especially wildfowl, such as geese, ducks, swans and sandhill cranes. All seemed to make the valley their feeding ground during the winter, and later during the spring blue grouse were in abundance.

We were all too busy that first winter to do much hunting. The house must be built, rails must be split and hauled to fence fields. Plowing must be done and crops planted, and we boys had that work to do. Ox teams we had in plenty, but plows had to be provided and fortunately my father was a blacksmith and plow maker, but had neither iron nor steel with which to make a plow, but had the iron for what was called a “Carey” plow, no doubt picked up on the plains. A Carey plow consisted of a small V shaped share or point welded to a short bar land side. All other parts of the plow, moldboard and all, was wood. The steel point would root up the ground, but most of the dirt would stick to the moldboard. This “Carey” plow and a wooden-toothed harrow comprised the farming implements of the early pioneers, but the rich virgin soils of our valleys only needed scratching to produce abundant crops.

Late in the fall of 1851 gold was discovered in Jackson County, and in the spring of 1852 there was a great rush to the mines and the valleys of the Umpqua and Rogue Rivers were rapidly settled up.